As I mentioned in my first February blog post, I weave, spin, dye, knit, do kumihimo, and mess around with just about anything else that one can do with fiber. As a consequence, when my husband and I travel outside of the United States, I’m always on the lookout for how other cultures work with fiber. This type of inquiry can lead me to interesting people and places and can influence how I work with fiber in my own studio.

Sometimes my inquiries can be as simple as finding a yarn store in in a city where we’re headed, as for example when we went to Copenhagen, Denmark. To find a yarn store, I consulted a great website, Knitmap, and came up with Sommerfuglen (which means Butterfly in Danish), a shop I could walk to from our hotel.

Sommerfuglen (Butterfly), a lovely little yarn shop in Copenhagen, Denmark

What I like most to find in shops when I travel is something produced locally. Happily, at Sommerfuglen, I found some undyed locally produced singles yarn (yarn with just one ply). Each package contained two skeins of the singles, which were quite substantially overtwisted. Overtwist yarns can produce interesting effects in both knitting and weaving, but that’s not what I was aiming for. Therefore, I rainbow dyed both skeins, plied them together to make a balanced (not overtwisted) two-ply yarn, and submitted it to our gallery for jurying. Thus, a little bit of Denmark ended up in the Potomac Fiber Arts Gallery in Alexandria, Virginia.

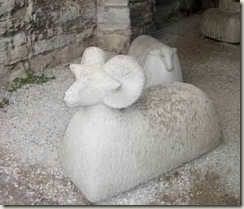

Later on that same trip, we stopped at Gotland, a Swedish island in the Baltic. Among other things, this island is known for a rare breed of sheep, appropriately called Gotland. Here’s what Wikipedia tells us about this breed. Images of sheep are everywhere on the island, including this:

Sheep as traffic bollard. This would not be a Gotland breed sheep, however, because Gotlands do not have horns

Sheep as traffic bollard. This would not be a Gotland breed sheep, however, because Gotlands do not have horns

I was lucky enough, while in Visby, the capital of Gotland, to find a shop where I could purchase a small amount (500g) of raw Gotland fleece. “Raw” in the context of spinning fiber, means the fleece exactly as it comes off the sheep, with the lanolin still in the wool. Since I’m not fond of processing fleece (scouring, carding, etc.), I sent it out for processing after we came home. Now it’s ready for me to spin into yarn, probably destined to be made into a sweater vest.

Gotland fleece, ready to spin. Compare this to the photo of the sheep in the Wikipedia article cited above.

Gotland fleece, ready to spin. Compare this to the photo of the sheep in the Wikipedia article cited above.

On a different trip, we found ourselves island hopping in the Pacific, more specifically in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). One of the islands we visited was Satawal, in Yap State. Yap is the one state in FSM where hand weaving as a day-to-day skill has survived. In addition, spinning a form of twine (for fishing nets and other purposes) is also done. On Satawal, the women weave, and the men spin.

The fiber the men use to make twine is a cocoanut fiber, and the technique they use is called thigh-spinning. The untwisted fiber is held in one hand, and with the other hand, the man rolls the fiber along his thigh to add the twist. As in all spinning, twist is needed strengthen the resulting fiber (twine, yarn, or whatever) and to hold it together.

Thigh-spinning twine for fish nets

Thigh-spinning twine for fish nets

Since I spin (on a spinning wheel), I asked if I could try. This led to great merriment among the Satawalese gathered around us because women simply do not spin. Note: I wasn’t very good at the technique.

The spun twine is wound onto a hand-hewn shuttle, which is then used while making the fishing nets.

Shuttle with cocoanut fiber twine

Netting shuttles are used in many places around the world, including in the US. Here’s a model that’s widely used in the US by tapestry weavers.

Both men and women in Satawal wear the same garment, a wrap-around skirt-like garment called a lava lava. Here’s a Wikipedia article on the lava lava. The women weave these garments, and the ones worn by women tend to be woven with bright stripes.

The weaving is done on a back-strap type of loom on a continuous warp, that is, a warp that wraps around the back beam and is tied back on itself. The back of the loom is braced against a wall, and the woman tensions the warp with a combination of leaning back against the backstrap and bracing her feet against the back of the loom.

Back-strap loom in Satawal. Note the weaver’s foot braced against the loom.

Back-strap loom in Satawal. Note the weaver’s foot braced against the loom.

The weaving is done in a communal weaving room, and the women all help one another.

A problem that transcends international boundaries: one weaver helps another repair a broken warp thread.

A problem that transcends international boundaries: one weaver helps another repair a broken warp thread.

On this wonderful visit to Satawal, I purchased several lava lava. Here’s one that I use as a table runner.

The narrow width defines this brightly striped lava lava as a child’s garment. An adult garment would be much wider so as to cover the woman’s thighs. While most women in Satawal are bare-breasted, showing a woman’s thighs is inappropriate in this culture.

The narrow width defines this brightly striped lava lava as a child’s garment. An adult garment would be much wider so as to cover the woman’s thighs. While most women in Satawal are bare-breasted, showing a woman’s thighs is inappropriate in this culture.

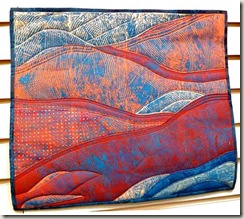

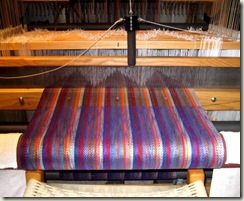

How might these lovely striped lava lava influence my own weaving? Here’s what’s currently on my loom:

Shawl warp on my 40-shaft AVL CompuDobby loom.

Shawl warp on my 40-shaft AVL CompuDobby loom.

This warp will produce five different shawls. The stripes will remain the same for each because they are built into the warp, but each shawl will have a different weft and a different treadling. Different treadlings produce different patterns, and different wefts can lend different colors and textures in the cloth. This gives each shawl an individual look.

Are these shawls influenced by the weaving I saw in Satawal? You decide!